A floating picket

At five in the afternoon on 3 August 1825, the shipbuilder and magistrate John Davison was summoned urgently to the Quayside Exchange on the banks of the Wear. A classical Georgian building completed in 1814, the Exchange was a symbol of Sunderland’s growing wealth and her position as one of the nation’s most important coal ports.

In August 1825, however, the trade of the bustling port was brought to a halt by striking seamen demanding higher wages and better working conditions.

A view up the River Wear. Coal ships and cobles (open boats) can be seen in the foreground while the harbour (left) and the North Sands (right) are visible in the background. George Hollis after Francis Swinburne, View of Sunderland, 1821

The Trustees of the British Museum

At the Exchange, Davison heard the complaints of captains and shipowners who told him that two large coal ships bound for London – Busy and Mary – had been surrounded and obstructed in the river by 60 sailors aboard seven cobels (open wooden boats). The shipowners and captains, aware of bad feeling among the sailors, had planned for trouble. They placed aboard their ships several constables to protect the crew from violence while Captain Hutchinson of the Mary issued his men with handspikes and armed himself with a pair of pistols.

Despite these preparations, the two ships got only a short way down the Wear before they encountered the seamen’s floating picket. When Hutchinson brandished his weapons, the unarmed sailors ‘show[ed] their breasts’ and dared him to fire. After an altercation with those aboard the Mary, the sailors focused their attention on the Busy, ‘which they commenced boarding’ and took possession of ‘by force’ before striking the sails, leaving her immobilised in the water.

Massacre on the North Sands

Retreating to Sunderland harbour on the south side of the Wear, Hutchinson met with fellow shipowners and pleaded for the support of the town’s authorities. Roused by their appeals, Davison declared he was ‘ready as a magistrate to discharge his duty’. He summoned from the town barracks a party of 24 soldiers from the Third Regiment of Light Dragoons and headed to the harbour to read the Riot Act to a crowd of ‘500-1,000 persons assembled on the south side of the river’.

Davison ordered Lieutenant Jebb to keep half his men on the south bank to ‘[k]eep back the crowd [that was] pouring in from all quarters to assist their Comrades on the River’. The other half of the dragoons were ordered to accompany Davison and his constables aboard three vessels attempting to go to sea. As the convoy cast off, Davison observed that the ‘ships in the Harbour … were thronged in the Rigging and Yards with People who assailed them with stones as they passed’. Davison therefore enlisted the support of the steam packet, Thomas & Dorothy, to pull the vessels clear.

As the authorities proceeded down the Wear, sailors aboard the Busy bombarded Davison and his retinue with lumps of coal, while a crowd of 100 men, women, and children threw stones from the North Sands, a spit of land 20 yards from a deep-water channel down which the ships had to pass to get to sea.

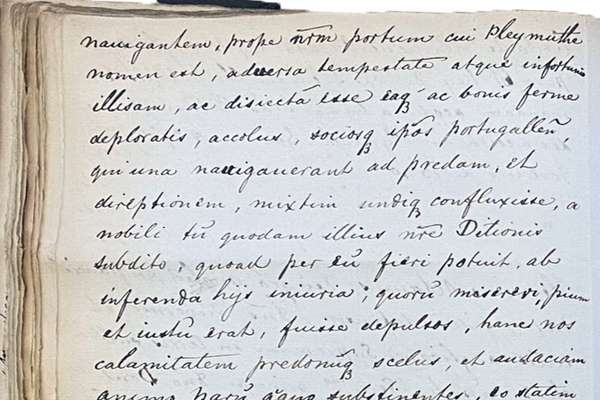

[The Riot then became so alarming by the Shouting Huzzaing and Stones] flying in all directions, that to prevent any further Injury witness thought it advisable to give direction to the Commanding Officer to have his men prepared in case of extreme Necessity to fire, they then proceeded further down the River and as they got nearly opposite to the Place called the Coble Slip, which is on the South Side, the Shower of Stones came so large and so frequent from the People on the North side, that witnesses resolved not only for his own personal safety but for the Rest of the Crew to consult with the Commanding Officer upon the Expediency of Firing, the Commanding officer thought it advisable that the Fire should be made high so as not to hurt any of the People about. They did fire in a high direction which witness believes after the first Fire did no Injury, but that it irritated the People more and the stones came in greater Quantity than before, if it was possible, That in consequence the Commanding Officer thought it possible Persons standing on the adjoining Hills might be injured by firing high and that firing low would be safer – after a few more guns were fired the mob began to disperse and they proceeded with the vessel to sea without further interruption. During the time of Firing the disorderly seamen began to separate, and on witnesses return up the river they found the People in a state of Quietness comparatively speaking and no stones thrown at them.

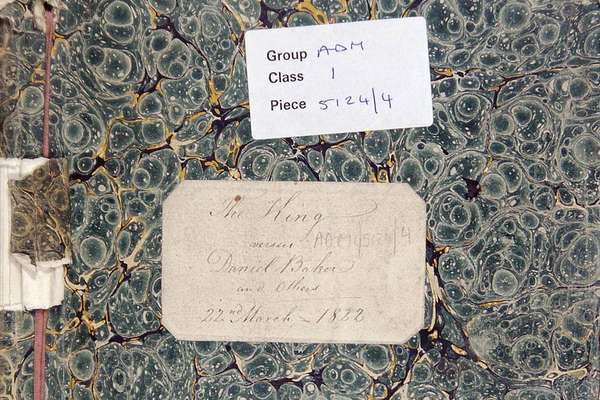

Extract of John Davison’s testimony at the Aird Inquest. Catalogue reference: DURH 17/73, Durham Spring Assizes (1826)

At this point, Davison claimed the ‘Riot … became so alarming by the Shouting, Huzzaing, and Stones flying in all directions, that to prevent any further injury’ to himself and the troops he ‘thought it advisable to give direction to the Commanding Officer to have his men prepared ... to fire’. After conferring with Davison, Lieutenant Phillips ordered his men to fire two volleys – the first over the heads of the crowd and the second directly at the protesters.

...Lt Phillips having with his Party got on board one of the Vessels proceeding to Sea, was assailed by such a Volley of Stones and Missiles from a large body of Seamen who had landed on the northern shore for the purpose and two or three of the Dragoons being severely struck, the Magistrate (Mr Davison) considered it necessary to order the Party to fire. About eight or seven carbines were discharged, and I am concerned to state from the crowd assembled there were reports to have been three killed and two wounded. Tho’ as yet I have received no authentic accounts. From the situation of the ground (being a steep declivity) I fear it is probable the report may be correct.

Extract of Lieutenant Jebb’s report to his Commanding Officer, Colonel Robert Manners of the 3rd Regiment of Light Dragoons. Catalogue reference: HO 40/18, f. 296

Three seafarers on the North Sands – Thomas Aird, Richard Wallace, and John Dover – were all shot dead. Four bystanders, including a 22-year-old shipwright Ralph Creighton and Mary Wilson, a woman in her seventies, were hit by stray musket balls and died of their injuries. These seven fatalities constituted the worst instance of state violence in the Northeast of England since the Hexham Massacre of 1761, which saw 52 killed by troops during anti-recruitment riots in the border town.

Seamen’s Union vs Shipowners’ Society

The bodies of Aird, Wallace, and Dover were brought to the south side of the river where a coroner’s inquest sat in the Justice’s Room at the Exchange. The handwritten proceedings taken down during the inquest provide valuable information for reconstructing what happened on 3 August but also offer some clues to the tensions in Sunderland in the run up to the massacre.

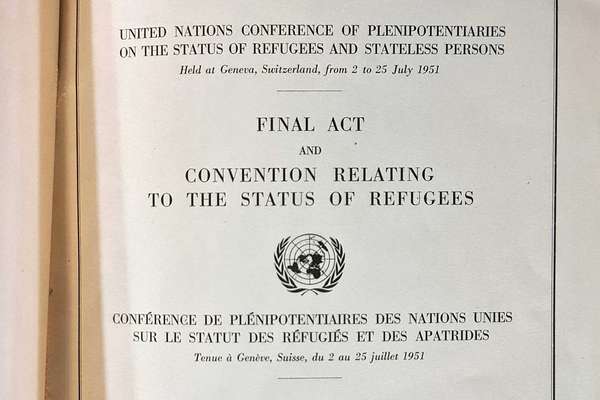

During the hearing, sailor Samuel Lappeg admitted that both he and the deceased, Robert Wallace, were members of a trades organisation – the Seamen’s Loyal Standard Association (LSA). The LSA was established at Shields in October 1824, following the repeal of the Combination Acts which, for the previous two decades, had proscribed striking and union organising as criminal offences. By December 1824, the LSA had over 1,200 members, with sailors from the Tyne and Wear paying regular subscriptions in exchange for pensions, sickness benefits, and insurance against the loss of personal possessions in the event of shipwreck.

John H. Richardson, a notary public from North Shields, however, wrote to the Home Secretary, Robert Peel, in January 1825 to warn him about the organisation. He claimed that the LSA was an alarming ‘combination’ ‘under the cloak of a charitable institution’ and that members were attempting to establish a closed shop by refusing ‘to allow any Seaman to be employed … until that man “joins the union”’.

Articles of Agreement between the members of the Seamen's Loyal Standard Association for the Tyne and the Wear, Resident in and near South Shields, in the County of Durham.

Sunderland: Printed by Reed and Son, High Street, 1825.

'Articles of Agreement’ issued to all new members of the Seamen’s Loyal Standard Association for the Tyne and Wear, 1825. Catalogue reference: HO 40/18, f. 137

The LSA’s printed ‘Articles of Agreement’ outwardly forbade ‘neglect of duty’ and the obstruction of vessels going to sea. However, their promotional materials show a determination to organise against low pay, unemployment, and various 'abuses' in the coal trade, including the dangerous practice of heaving ballast at sea.

Over the Spring of 1825, the LSA was campaigning against the dire effects of poor conditions, low pay, and shipwreck on their members. Meanwhile, their employers formed a ‘counter combination’ in the form of the Ship Owners’ Protecting Society to break the influence of LSA through the establishment of a register office as a means of bypassing union labour.

Signatures of the ‘merchants, shipowners, and tradesmen of the town of Sunderland’ who requested a permanent military force to tackle the ‘riotous and insubordinate conduct’ of the town's seamen. Catalogue reference: HO 40/18, f. 286

By the late summer, several hundred sailors were out of work, and tensions were mounting in Sunderland. On 25 July 1825, the shipowners contacted the Home Office to complain about the ‘very insubordinate and riotous conduct of seamen and others’. They pleaded with the Home Secretary for a ‘permanent military force to be established in the town’.

Subsequently, in an attempt to reach a deal with the shipowners, the seamen put forward a three-part proposal calling for the abolition of the register office, the preferential employment of LSA members, and the payment of an additional shilling in wages for the heaving of ballast. Although this initiative had the support of the shipowner Robert Scurfield, it was rejected by the shipowners’ society on 2 August.

It was this breakdown of negotiations which led to the strike that preceded the North Sands massacre.

‘Justifiable homicide’

In the aftermath of the killings, events moved rapidly.

On 5 August, the coroner’s inquest on the bodies of Aird, Wallace, and Dover gave a ruling of ‘justifiable homicide’. The inquest held on the body of Ralph Creighton at Monkwearmouth, who was ‘shot off his stage’ while at his trade of shipbuilding, brought in a verdict of ‘accidental death’. No further inquests were held.

According to an open letter issued by the LSA, the bodies of the three sailors were escorted by an immense funeral cortege and interred in a single grave at Holy Trinity Church on 6 August. ‘[H]ardly a dry cheek was to be seen; and a spectacle so melancholy was never before witnessed in Sunderland’ (LSA, ‘To the Secretary of State’, The Times, 12 August 1825).

Meanwhile John Davison and ‘two of the most respectable ship-owners’ were dispatched to London with a letter for the Home Secretary, informing him about ‘the attempt of the sailors’ but reassuring him that patrols by the dragoons and the arrival of the naval cutter HMS Swan had restored the peace of the town.

Although there was a mild controversy over whether Davison ought to have read the Riot Act on the North as well as the South side of the Wear, newspaper editors generally approved of the action taken by the magistrates and the military. The Morning Post praised Davison’s bravery in carrying out a ‘very painful public duty’. Peel agreed that he was ‘fully justified’ in his actions and recognized the ‘coolness of the Troops under the provocation to which they were exposed’.

Arrests and prosecutions

At the same time, the Home Secretary was eager for the shipowners and magistrates in Sunderland to bring the ringleaders of the strike action to justice. Prosecutions were sought under the Shipping Act of 1793 which gave magistrates at the Quarter Sessions powers to impose a prison sentence of 6-12 months on sailors who used force to obstruct the sailing of any vessel.

To encourage informants to come forward, the Home Office ensured that an advertisement was circulated in the London Gazette offering £100 ‘for each offender who shall be convicted’. Sunderland’s shipowners, keen to break the spirits of the LSA, communicated to Peel that it was their ‘anxious desire to discover and bring those persons to justice’. However, they remarked that this was difficult because of the ‘nature and extent of the Seamen’s Union’ and the depth of their influence in Sunderland.

His Majesty being sensible of the mischievous consequences which must inevitably arise from such illegal and dangerous proceedings, if not speedily suppressed ... is hereby pleased to promise His most gracious pardon to any person or persons who have been concerned in the illegal proceedings before mentioned (except those who have committed or offered actual violence) who shall give such full information against others who have been also concerned in them as shall lead to their apprehension and conviction.

And, as a further encouragement, His Majesty is hereby pleased to promise to any person or persons (except as aforesaid) who shall discover and apprehend, or cause to be discovered and apprehended, the authors, abettors, or perpetrators of any of the illegal proceedings before mentioned, so that they or any of them may be duly convicted thereof, the sum of ONE HUNDRED POUNDS for each and every person so convicted ; the said sum to be paid by the Lords Commissioners of His Majesty's Treasury. R. PEEL.

Reward advertisement in the London Gazette, 10 August 1825, p. 1482. Catalogue reference: ZJ 1/168

Over the course of three successive Durham Quarter Sessions (Oct 1825-May 1826), 12 sailors were brought to trial and convicted for obstructing the Busy on 3 August. Together they were sentenced to 71 months imprisonment (or nearly 6 years in total). Some of the men with aggravating circumstances, like David Bell who had assaulted a special constable, were subjected to additional hard labour.

Legacy

The repression of the seamen’s strike of August 1825 left seven people dead and a dozen seamen in prison. However, the sailors remained undaunted. The LSA continued to operate as a friendly society well into the 19th century, before it was finally dissolved in 1894.

In its attempts to organise a disparate labour force and to put pressure on the shipowners to improve wages and conditions, the LSA laid the groundwork for the development of later maritime unions, whose struggles would continue well into the 20th century.

At the same time, the blood that was shed on the North Sands was more than a footnote in labour history. The seamen viewed it as a communal catastrophe that demanded an official investigation (LSA, ‘To the Secretary of State’, The Times, 12 August 1825). However, once the coroner’s jury had found the killings to be a justifiable response to an illegal riverside riot the seamen had no recourse.

Thanks to surviving inquest records and government correspondence, we can begin to recover the experiences of the Sunderland sailors and reflect on the sharpness of industrial relations, and the draconian use of state violence in the Northeast of England two centuries ago.

Records featured in this article

-

- From our collection

- DURH 17/73

- Title

- Durham assize records

- Date

- 1826 Spring

-

- From our collection

- HO 17/87

- Title

- Home Office criminal petitions

- Date

- 1821-1832

-

- From our collection

- HO 40/18

- Title

- Home Office: Disturbances Correspondence

- Date

- 1823-1825

Further reading

Stephen Jones, ‘Community and Organisation – Early Seamen’s Trade Unionism on the North East Coast, 1768-1844’, Maritime History vol. 3 (1973), 35-66.

D.J. Rowe, ‘A trade union of the North East coast seamen in 1825’, Economic History Review, 2nd ser., 25 (1972), 81-98.

David Gordon Scott, ‘'The Never To be Forgotten, 3rd August' - North Sands Massacre, Sunderland, 1825’, HERC Blog (Open University, 2025). [accessed 22 July 2025]

Bill Wildish, The Sunderland Seamen’s Strike of 1825 - ‘The Long Stick’, Sunderland Antiquarian Society (November 2024).